History doesn’t repeat itself, but often it rhymes

Simon Goodwin’s tenure as coach can, more than any other, be defined by a rule. Fitting for the coach of the Demons that this rule would be 6-6-6.

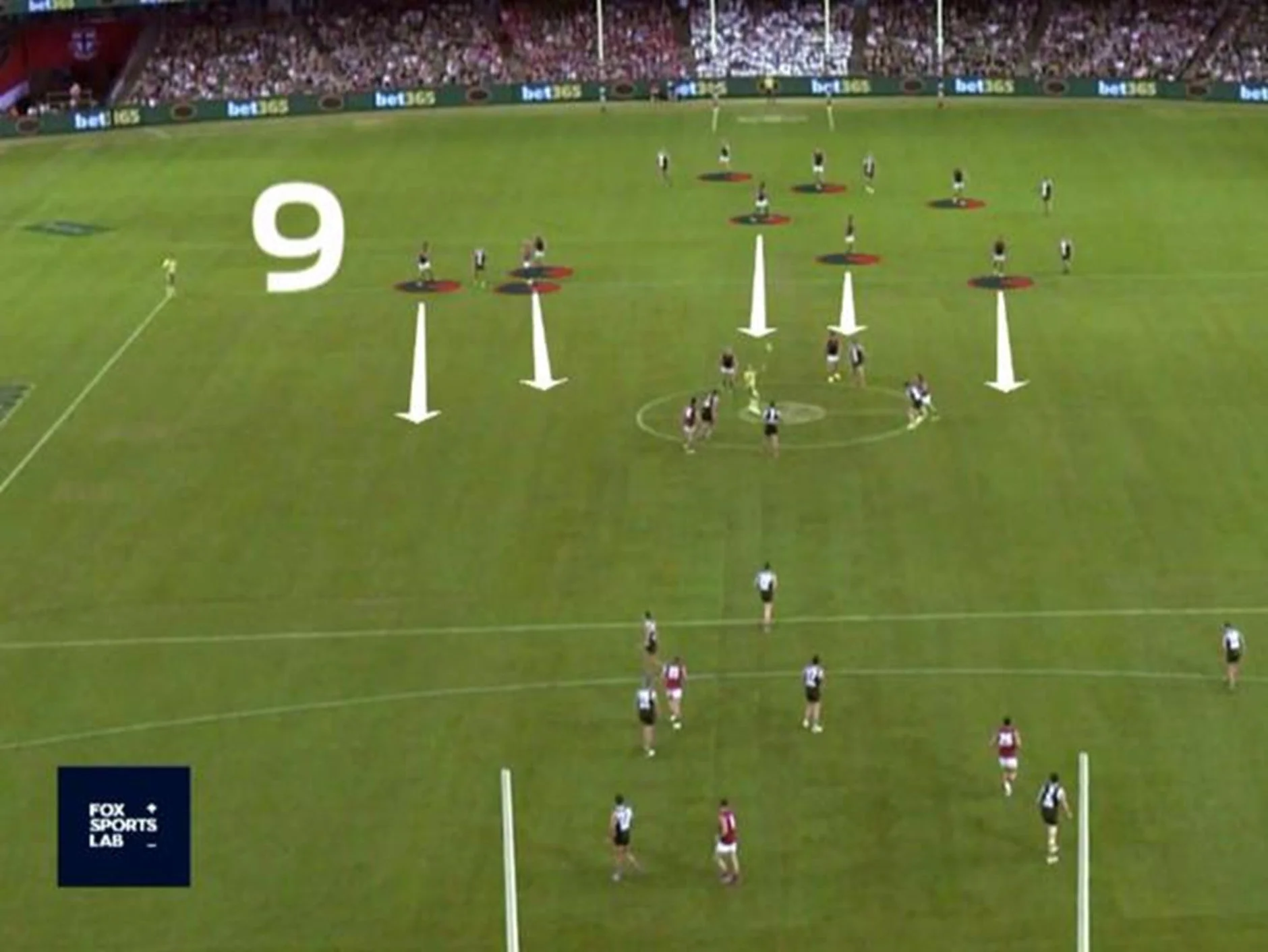

Round 1 2017 – Simon Goodwin’s first game as Melbourne Coach. The Demons take on Alan Richardson’s St Kilda. All time Saints great Nick Riewoldt kicks two goals in the first quarter continuing his long-running torment of Melbourne. The 6-6-6 rule isn’t even a gleam in Steve Hockings eye and Goodwin has up to 9 players starting in defence at times. This isn’t a flooding strategy though - as the ball bounces they move into the centre square to provide attacking options. It sees them win 10 consecutive centre clearances and helps turn the match with a run of 10 goals.

Source: Fox Sports

Four years later and as far away from a Round 1 twilight game at Docklands as you can get – the 2021 Grand Final in Perth. We turn to the middle of the match. Marcus Bontempelli has put his Bulldogs three goals up and Melbourne are on the ropes. A goal to Bayley Fritsch sees the margin closed and the ball returned to the centre. In less than a minute of game time the Demons rip the ball out of the middle and score a further two. Even more astoundingly, ten minutes later they do the same again, scoring three goals in the final minute of the quarter.

The 6-6-6 rule means nowhere to hide and few ways for the Dogs to mitigate the damage. The result is the most astounding display of pure football since the peak of Geelong’s time under Mark Thompson, and possibly ever. Melbourne score 100 of the last 107 points of the match and Goodwin breaks the longest active premiership drought in the league.

We move forward another four years, but like many stories we return to where it started. Docklands. Twilight time-slot. The opponents are once again St Kilda, although faces have changed or moved roles. Alan Richardson now plays confidant to Goodwin rather than competitor. Nick Riewoldt provides commentary as Nasiah Wanganeen-Milera anoints himself as the heir to St Nick in the St Kilda mythos with two last quarter goals.

Like the Bulldogs four years prior, Melbourne finds their options limited in blunting a withering 9-goal onslaught. However, 6-6-6 still has an even more central role to play. Melbourne goes where few teams before have tread, and none with such dire consequences. They concede a free kick for a 6-6-6 infringement at the final centre bounce with scores tied. This leads to a Wanganeen-Milera mark and a goal after the siren to seal Goodwin’s fate.

He would go on to coach the following week, and Brad Green denies the result played a part in his sacking, but it’s plain to see this is where Goodwin’s career at Melbourne was decided

Throughout Goodwin’s coaching tenure his contribution to his game and club have continually and unfairly been diminished. Now is as good a time as any to look at his legacy.

Taking the team to a preliminary final in 2018 was largely credited to the framework Paul Roos set up. Make no mistake though, this was light years away from anything Roos had coached.

People finally gave Goodwin ownership of results when Melbourne finished in the bottom two the following year.

The ultimate success of 2021 was attributed to hyperbolic assessment of Melbourne as one of the greatest playing lists ever assembled. Yet it was seen as Goodwin’s responsibility when those same players kicked themselves out of consecutive finals in 2023.

Simon Goodwin took over from one of the more defensively-minded coaches of the modern era. Within two seasons he had forged the team into one of the most potent offences we’ve seen in a decade. He was then able to transform it once again into one of the greatest defensive sides in the game’s history. Most coaches don’t succeed in one style, yet Goodwin appears to be criticised more than anything else for not being able to guide a playing group through a third successful metamorphosis.

Attack to defence

David King’s analysis of Goodwin’s first match officially in charge heralded this as a new look – numbers behind the ball to generate rather than stymie attack.

Goodwin wasn’t alone in using unconventional centre bounce setups through 2017-18 – Richmond, Adelaide, and North Melbourne each strayed from 6-6-6 more frequently in 2018. He was however a noted early mover and the results were significant.

Goodwin also had something none of those other coaches had – Max Gawn.

He correctly backed Gawn to give them great starting position. By the time the plan had matured in 2018 Max was getting a hitout to advantage from 22.4% of ruck contests he attended compared to a league average of 13%. If they were getting first hands on it, having the players running through off the back of the square would create havoc for the opposition, offering multiple lanes to attack resulting in a league high 14.6 marks inside 50 per game (Only 2022’s Geelong bettering that figure since).

Then between the 2018 and 2019 seasons the AFL brought in the 6-6-6 rule. Ostensibly this was to reduce the ability of teams to defend a lead by flooding numbers backwards. For Melbourne the impact was the reverse. From 2018 to 2023 points from centre bounce went up across the league but down for Melbourne, bringing the demons from +5.3 points vs the average to within 0.2 of it. Similarly, Melbourne’s advantage in marks from inside 50 would also evaporate over this time.

It’s worth noting as a comparison that Adelaide faced a similar challenge. Their tactics were affected similarly by the introduction of 6-6-6. 2025 will be the first year since their 2017 grand final and minor premiership that they finish above 10th.

The rule change alone can’t be blamed. Melbourne’s primary target up front, Jesse Hogan, went home to Perth after the 2018 season. Melbourne spent the capital gained from Hogan’s departure to bring in Gold Coast captain Steven May. Melbourne were pilloried for high-priced acquisitions of key defenders in consecutive seasons. Despite common wisdom being that defence wins more premierships than offence, paying for defenders seemed the greatest offense of all.

“They’ve gone May and Lever as part of their big spend, who are very good players, but what influence can they really have on winning games of football?”

Goodwin and his supporting team had correctly identified that in Gawn they not only had an elite ruck, but an imposing behind the ball presence. Coupled with May and Lever, and supported by pressure on the ball, they would form a wall that few teams from 2021-2023 were able to penetrate. This would be the best version of Simon Goodwin’s Melbourne – suffocating the opponent by controlling territory and denying the opportunity to convert possession into scoring.

Another deployment of resources from attack to defence is worth noting – Highly regarded assistant Troy Chaplin. Chaplin started as a forwards/offence coach, but by 2021 had transitioned to defence and that’s where he won and finished runner up in the AFLCA Assistant Coach of the Year Award. This year saw him moved back to the forward line, perhaps indicating another shift in overall game style from Goodwin, though ultimately not one he would see out. Chaplin has since been appointed caretaker coach for the remaining three games.

A dynasty gone begging

Much is made of the idea of a wasted dynasty at Melbourne under Goodwin. This argument is absurd. Goodwin achieved what only three other coaches have, and none for six decades before him – bringing the Melbourne Football Club to the top of the mountain. Many of the same critics pushing this narrative now, were deriding the state of the list in 2020 and arguing that Melbourne had severely over-estimated the talent it had available.

Across the entirety of 2021-2023 Melbourne spent a total of two rounds outside the top 4. This included an unbroken two years, bettered in the AFL era only by Essendon across 1999-2002. They dominated the 2021 finals series with margins of 33, 83, and 74. In 2022 both finals saw them in winnable positions, up by three goals in the second quarter against Sydney and five goals just before half time against Brisbane.

2023 saw them lose to eventual premiers Collingwood by 7 points. Errant kicking and a career ending injury to Angus Brayshaw early in the match proving impactful. The following week against Carlton they surrendered a lead late while kicking 9.17 and losing by just two points.

Football is like poker. There are elements outside your control, but you can make sure the decisions you’re making leave you in a winnable position. Goodwin’s game plan consistently put Melbourne in a position to win. In 2021 the cards fell for him, the following two years they didn’t. That shouldn’t invalidate the process behind it.

The final act

2025 has been a curious year as a Demons supporter. While the results speak for themselves, it’s possible to read either optimism or pessimism into the broader picture.

Melbourne came in with high internal expectations. They had also traded their 2025 first round pick away to help secure Xavier Lindsay and Harvey Langford in the previous draft.

It was a surprise then that they named 5 debutants for their Round 1 match vs GWS. Excluding the first matches played by a new club, only three teams have named five debutants in the AFL era – Melbourne in 2025, Collingwood in 1995, and Richmond in 1993 – all in Round 1. The team got within a kick and arguably should have won.

If Round 1 was a surprise Round 2 was a seismic shock. A dismal 10 goal loss to the Kangaroos, who they previously hadn’t lost to since 2019. The result was comprehensive enough for pundits to declare that not only had North Melbourne finally arrived, but that Tristan Xerri had taken the mantle of best ruck in the competition from Gawn. Both claims would prove premature.

Melbourne limped to 0-5 with a percentage of 60 before a 6-week uptick in form saw them recover to 5-6. The most impressive performance was a two goal win against the reigning premiers Brisbane at the Gabba, having trailed all day.

The next three matches saw them lose comfortably against fellow bottom-dwellers Port Adelaide and St Kilda, yet come within a point of beating Collingwood.

To Round 19 Melbourne had been fairly unadventurous with it’s centre bounce mix. 84% of its total centre bounce attendances were taken up by the top 5 players, second only to Gold Coast. With the exception of Kysaiah Pickett’s move into the midfield, the names were familiar – Gawn, Petracca, Oliver, Viney.

Caleb Windsor has finally seen some time at the coalface since then, but arguably the picture is even more static over the last 5 weeks. Only 8 Melbourne players have attended a centre bounce in that period – this includes 2 attendances by Xavier Lindsay and Jacob van Rooyen relieving Gawn in the Ruck. The season has been dead for a long time, but Goodwin has likely been coaching for results out of necessity. In doing so he has gone back to the old guard. It’s hasn’t given a great look at what the midfield of tomorrow will eventually be. It also hasn’t provided results. You can’t afford to waste a game in footy. I’d argue that’s what the tail end of this season has largely been.

The attitude to selection has faced similar criticism. Established players have been given leeway despite poor form while fresher faces have seen a revolving door. To some degree this is understandable. The older players have a body of work to show what they can return to. Goodwin trusts them to reach that level again. However, this needs to be balanced with allowing younger players to find their feet in a team.

Excluding injuries and suspension, each of these players have been given single-match selection stints at AFL level this season: Turner (twice), Langford, Woewodin, Johnson, Howes, van Rooyen, Jefferson, Laurie, Tholstrup, and Sharp.

Laurie’s only game for the season saw him named Substitute and get just 20% time on ground before being dropped again the following week. Similarly Taj Woewodin and Harvey Langford saw single-week call-ups used as the sub, although Langford has since cemented his spot in the side.

From the outside it looks like the club was pulled in two different and incompatible directions. Elements saw this as the launching pad for a list refresh, while the mounting pressure on Goodwin seemed to have him coaching for the result week by week. In the end neither side got what they wanted.

The end should not be the whole of it though. Simon Goodwin made huge achievements in his time at Melbourne. I’ll never forget sitting in 90,000+ crowds in the finals against Geelong and Hawthorn in 2018. The images of the 2021 Grand Final will forever be etched in my mind, even if I didn’t really believe we were safe until Luke Jackson put us 10 goals clear 24 minutes into the final quarter.

I feel an immense and enduring sense of gratitude to Simon Goodwin and a love for his era as coach. I could turn up week in week out knowing I was going to see a truly elite team perform. While I’m sure there are raw and deep wounds now, I hope more than anything that in time he’ll feel that fondness and take great pride in what he has done.

I also hope that the club leadership recognises that trusting a process to identify the best assistant coach available is almost universally a better option than going for a big name. We needed Paul Roos when he was appointed, not so much for his coaching ability but for the stability he provided. We were at ground zero as an organisation and needed a rock to build on. I hope we’ve come somewhat past that and can look not just to survival, but to success as we did when handing the reins over to Goody.